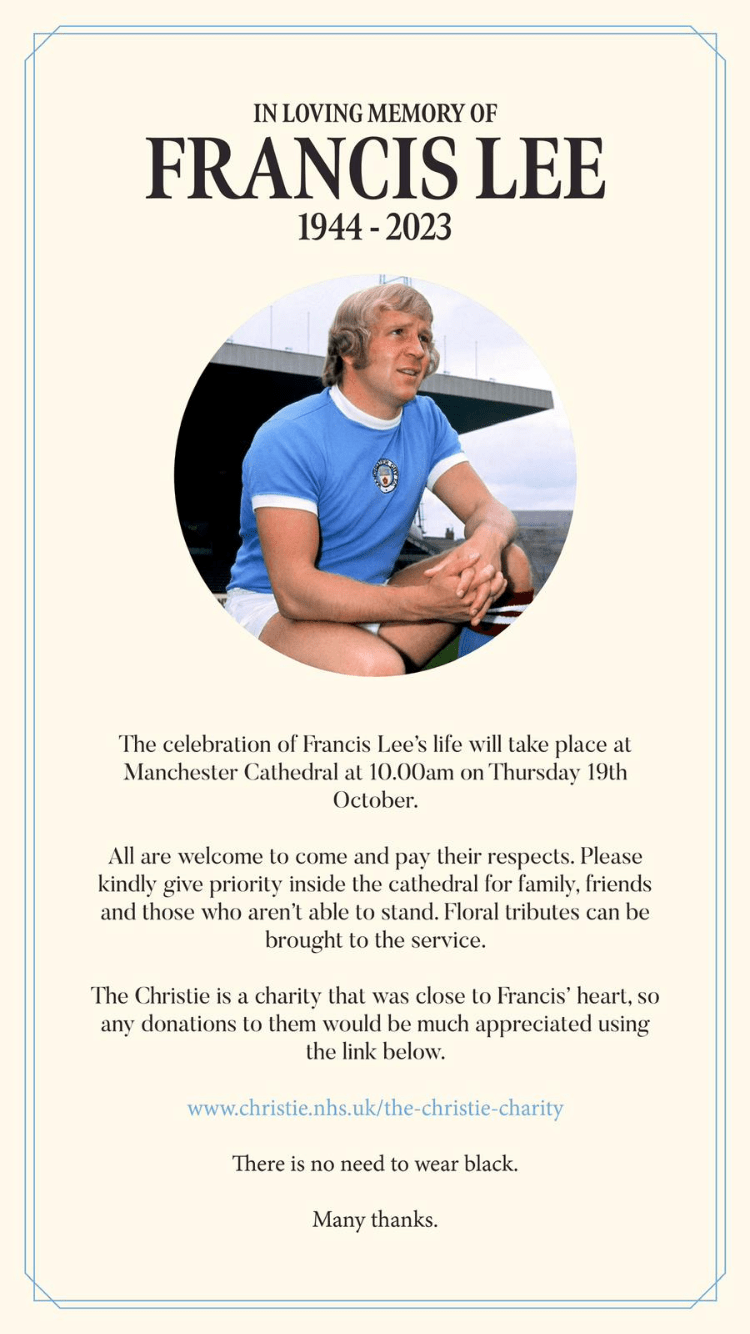

Today was an emotional day but it was also a perfect sendoff for Francis Lee. I was at Manchester Cathedral to pay my respects and it was great hearing the tributes to Francis today, particularly the one from Will Perry and Francis’s son Jonny. They did him proud. Great to see many Blues & former players there, plus Barry ‘look at his face’ Davies. The former players from City included Mike Summerbee of course, Tony Book, Micah Richards, Peter Barnes, Tommy Booth, Asa Hartford, Joe Royle and Alan Oakes. Former physio Roy Bailey was there, as was Fred Eyre, and playing representatives of Bolton and Derby. Colin Bell’s son Jon was also present which was fantastic to see.

One of the things that came across well from Jonny’s eulogy was his dad’s sense of humour. Jonny revealed how Franny often told interviewers fake facts like how he could play the piano to classical concert standard and some of these jokes have made it into obituaries. Brilliant – it also means I now need to go back through my interviews with him to see if I can spot any Franny wind ups!

Franny’s mate John Gildersleeve also revealed how the two of them were travelling back from a holiday in Dubai when Franny (MCFC chairman at the time) received a phone call from BBC Radio Manchester. The interviewer knew that Franny had been out of the country but didn’t know where and asked if he’d been trying to sign a player. Franny said he had and that the Blues were in negotiation to buy a strong relatively unknown defender. He said that he couldn’t say much but he could reveal the player’s name. He then gave the BBC a Dutch sounding version of John Gildersleeve’s name – and according to the tale we heard the BBC fell for it!

The service included Blue Moon played on the cathedral organ (quite emotional) and recordings of What a Wonderful Life (Louis Armstrong) and You Got It (Roy Orbison), plus hymns Dear Lord and Father of Mankind and, of course, Abide With Me. As well as family and friends, City’s Danny Wilson added to the eulogies with an appropriate and appreciated contribution about what Franny meant to City.

In addition to family, friends, colleagues and former players there were many, many fans there paying their respects. I think Francis would’ve loved that.

After the service at the Cathedral there was a private family cremation and other commemorations marking Franny’s life.

Franny was a wonderful player, businessman and man. Today Manchester and the world recognised that.

If you missed reading my interview with Francis from 2010 you can read it below. For those who wonder why Francis was so significant hopefully this will give an indication. This is one of many interviews I did with Francis over the decades and I want to include this one today as it was written up as a Q&A style piece with Francis’ own words documented. I hope it captures the spirit of the legendary Bolton, City, Derby and England player.

IN SEARCH OF THE BLUES – Francis Lee

For today’s feature author Gary James met up with former Bolton, City and England star Francis Lee. In a glittering career Francis won two League Championships, the ECWC, League Cup and the FA Cup.

Francis, let’s begin with your early career at Bolton. Can you explain how that started?

I was a member of the groundstaff and I set myself a target that I had to get into the first team by the time I was 17 or 18 and if I didn’t I was going to go back to college and train as a draughtsman. That was my plan, but I managed to get into the first team at 16 and I made my debut against City (5/11/60). We won 3-1 and I scored a header at 3.15 against Bert Trautmann – I think Bert must have thought he was getting over the hill for me to score a header past him! It was a great day and there were some very good players on both sides – Nat Lofthouse of course. Ken Barnes and Denis Law were playing for City.

I kept my place for about six games and then the following season I had 5 games, then in 1962-63 I was top scorer with 12 goals from 23 League games.

You were playing out on the wing those days and topped the goalscoring charts each season at Bolton from 1962 until you left. Was that your preferred position?

I think my best position was as support striker to a big fella. I only played in that role twice really – at Bolton with Wyn Davies when I scored 23 League goals one season and then at City with Wyn again when I scored 33 League goals in 1971-72. A lot of my career was spent at centre-forward at City and at Derby which is a bit of a difficult position to play if you’re only 5ft 7. When I played for England I was support to Geoff Hurst and that suited me. When I played at centre-forward I had my back to the ball but when I was support striker – the free player – that suited me fine. I could pick up the ball going forward and that was great.

At Bolton you scored 106 goals in 210 appearances. A great record, but when you left the club the stories were that you were in dispute. Is that true?

Well, what happened is that Bolton had got relegated in 1964 and, despite a near-miss in 1965 when we finished third, it didn’t feel as if we were going forward. My ambition was still to see how far I could develop in the game and in the back of my mind I had the ambition to play for England, but I wasn’t even selected for the under 23s. The story was going around that I was difficult to handle – which is funny because Joe Mercer said that I was the easiest player to handle at one point.

At one point I remember asking the manager why I wasn’t earning as much as Wyn Davies who had been brought in to score goals. I was top goalscorer but Wyn was paid more and the manager said: “you’re too young!” but Wyn was only about a year older than me.

Were you difficult to handle at Bolton?

I was opinionated and ambitious, but not difficult. I think that message was going around because I was on a weekly contract at that time and the club knew that it would be difficult for them to stop me moving on if another club came in. So any player with a reputation for being difficult would not be on anyone else’s shopping list, would they? Bolton offered me a new contract worth something like £150 a week but before that I was on £35. That actually upset me more and I said: “if you now think I’m worth £150 a week what about all those years you’ve been underpaying me?” It wasn’t the money that was an issue it was the way they handled it. What they were doing was trying to get me on that contract and then my value would increase if someone came in to buy me. Once they saw how dissatisfied I was with the way they were handling it, they said that it’d be best if we made a clean break, and so I said I’d pack the game in. I had my business by then and so I said: “give me my employment cards and I’ll pack it in.” They thought I was bluffing.

It’d been a decent season so far – I’d scored 9 goals in 11 games including when we beat the great Liverpool side in the League Cup – but then it all stopped in September 1967. They gave me my cards and that was it.

Were you absolutely certain you’d pack it all in at that point?

I kept myself fit but I was working on my business. I was driving my lorry around, collecting the waste paper and so on. The business was growing and I felt that if I wasn’t wanted then I’d concentrate on that. It was always my fallback. It was only a small business really.

I know how stories can get exaggerated over the years, but is it true that in between games you were going around collecting the waste paper?

I used to drive my lorry during the week and even on the Thursday or Friday before a game I’d be collecting waste paper. I used to put on a flat cap and muffler so that nobody would recognise me! In summer I worked long hours and I was earning more in the summer months than I was playing football in Division One. I also played cricket. At one point it looked like I was going to be a footballer and cricketer but the season overlap meant I had to concentrate on football.

In the end I was driving articulated lorries and it was getting to be a very good business. My last job was the day before I signed for City! I roped and sheeted about 15 ton of paper and cardboard from a spinning mill in Bolton. Took it to the Sun Paper Mill in Blackburn and when I got back about 5pm I got a call from Joe Mercer. He didn’t give his name at first but I recognised him and he said: “Where’ve you been?” I told him I’d been playing golf – I couldn’t play the game at all then but I couldn’t tell him what I had been doing! I asked him: “who is that?” He said: “Tom Jones.” I said: “It doesn’t sound like Tom Jones, sounds more like a man called Mercer!”

Did you immediately want to sign for City?

Other teams had shown interest in signing me. Liverpool offered £100,000 I understand but then when I wasn’t playing it affected my price. In later years Shanks often used to grab me and say in that strong Scottish accent: “Son, I should’ve signed ya the night I saw ya!”

City was just right of course. It meant the business could carry on. I don’t know if Bolton had told Joe about my contract or the £150 offer but the first thing he said to me before we talked it through was: “I’ll be honest with you son. We’ve no money. We’re skint!” I said: “It doesn’t matter. I’ll just be delighted to start playing again.”

I signed for City for £60 a week – remember I’d turned down £150 at Bolton – and in the end it was well worth it. The way the team developed and, of course, when I realised my ambition and played for England.

City paid £60,000 – actually they paid £40,000 down and £20,000 on the drip! I was told I should get about 5% of the fee but then the League wouldn’t allow it because I’d left under strained circumstances or something.

I left a lot of friends of mine at Bolton – Freddie Hill, a great friend, Tommy Banks, Roy Hartle, Gordon Taylor – and we had some great times. Those of us who had come through the ranks were poorly paid for the job we were doing at the time, but we enjoyed ourselves. I never had any argument with the players, fans or people at Bolton, it was just those that ran it. I loved my time at Bolton.

When you joined City the Blues were ninth in Division One after losing 5 of the 11 games played. But the side was transformed from the moment you came. Unbeaten in your first 11 League games. Were you the difference?

The team just clicked and I was only part of a good group of players. We had that great run up to Christmas, then a bit of a blip, but in the New Year we just rattled on. It was a terrific period. Mike Summerbee was playing at centre-forward and our culture at the time was to play with five forwards. It was very unusual for the time. The only system we played was that we all played we had ten players who went up together, and ten who defended together. When we won the League at Newcastle at the end of the season it was wonderful and particularly special because none of us had ever won anything significant. This was our first major success and that’s why the following season the ordeal of playing a European Cup tie was so tough.

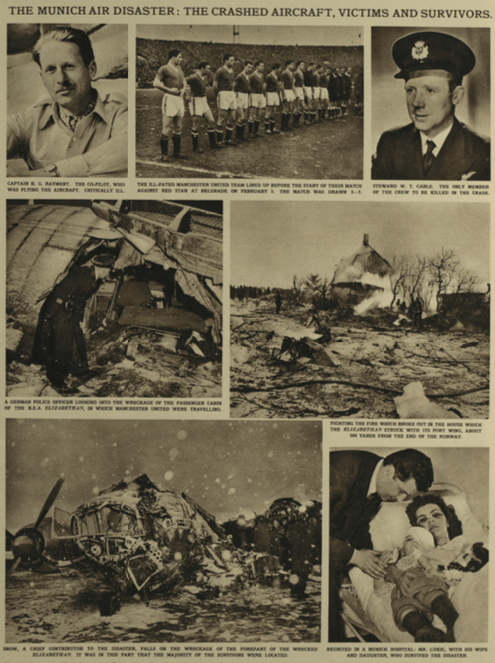

Was it just inexperience that caused City to lose the Fenerbahce European Cup tie 2-1 on aggregate?

None of us had played in Europe before. Mike Summerbee had only made his England debut against Scotland in February 1968. Colin Bell had played in two England friendlies, but apart from that none of us had any concept of what it could be like in Turkey. Had we played the first leg in Istanbul and the second at Maine Road I think we’d have gone through, but the goalless 1st leg at Maine Road killed us really. We worked hard in Istanbul and it was a creditable result over there but we were out and it was because we were inexperienced. It was a culture shock.

Despite the Fenerbahce setback did it feel as if City could find further success?

No confidence was at a real low after that game. We’d had a bad run and only had a small squad so we struggled. But that was the way it was. Most clubs had small squads but what Shankly used to do at Liverpool was sign a couple of players each season just to ensure that those who were first choice felt the pressure and remained hungry for the game. Back then the motivation for all of us was to be in the team and to keep your place. The money was significantly different if you lost your place – City used to have this thing where we’d get a bonus depending on the size of the attendance as well as goals, wins and so on. That motivated you to ensure you did all you could to entertain as well as win – you wanted the crowds to grow.

Effectively you could double your wage by simply being in the team. That’s a big incentive.

You mentioned about squad size, I think younger readers may be surprised to read that City tried to keep the same eleven players game after game, competition after competition. Would you have enjoyed a squad rotation policy when you played?

The aim of a footballer is to play. Why would anyone want to be rested? If a manager had said to me ten minutes before full time that he wanted to bring me off even though I was playing well, I’d have told him “no way! I’m enjoying myself. This is what you bought me for, now let me do it!” It wouldn’t matter what the manager says I’d want to stay on. That’s what the game is about – enjoyment! Every player wanted to play. None of us wanted to be on the bench.

People talk about the number of games played today but in 1969-70, ignoring domestic friendlies and the Charity Shield, you played 71 competitive games for England and City. Would squad rotation have helped?

No. Playing is always better than being on the training pitch and I used to love playing, so I tried not to miss a game. It didn’t matter whether it was an England friendly, Anglo-Italian cup or whatever, I wanted to play and represent my club and my country. I think it’s best for all players. Look at Tevez. He’s improved his fitness and form by playing, and I think a lot of players are like that. He needs to play, and that’s what I always wanted.

Some of the other players from the 1969-70 season have talked about Franny’s Grand Slam. Your aim to win four trophies in one season inspired them. What do you remember of that?

Well, we wanted to win every game so it seemed natural to me that we should go for all four. We won the League Cup and Cup Winners’ Cup, so that wasn’t bad. In the FA Cup we were odds on to win at Old Trafford because we’d beaten them so many times. We ended up suffering a rare defeat at United, but it was one of those we should really have won based on form and everything. We were doing okay in the League then we had a few injuries – Mike, Colin Bell and Neil Young were injured at key times – otherwise I think we would have won three trophies. But the thing about the ‘Grand Slam’ was that it was the ambition of the place. I remember we were going to London on the train and could see Wembley, and I shouted to the lads to take a look because two of our ‘Grand Slam’ games would be played there!

Moving forward a couple of years, the success started to disappear. There had been the takeover that ultimately led to Peter Swales being Chairman, and of course we missed the title by a point in 1972. What had changed?

Rodney Marsh has told you himself that his signing made a difference. Malcolm played Rodney and disrupted a team that I’m convinced would have won the League that year. Derby won it when they were in Majorca or somewhere! I don’t blame Rodney… that season our luck changed and everything went against us. There was one game near the end where we should have had a couple of penalties for hand ball but because this was the season when we got that record number of penalties they weren’t given.

Thinking about the penalties, a lot has been made about you ‘diving’ but the factual evidence is that the majority of penalties were given for things like handball or fouls on other players. Nevertheless, the myths survive. So, big question, did you ever dive?

I couldn’t say that I always stayed on my feet unless I was absolutely knocked down. In those days you used to get some horrendous treatment by the defenders, but I will tell you that the season before those penalties we only had a couple, and before that I think it was one. The reason we got so many in 1971-72 is that they had changed the law, plus we were going for the title so we were putting sides under a lot of pressure and they reacted. I was fouled only 5 times out of the 13 league penalties we got.

When I was attacking I used to play the odds. If a defender was coming towards me I’d carry on, or I’d run towards the defender because there were only three things that could happen – he pulls me down, he gets the ball of me – well done, or I get a cracking shot at goal. So the odds were in my favour. You have to play them.

I think the reason people go on about penalties with me is because I was the one taking them. It didn’t seem to matter what they were given for, the headlines were that I had scored from a penalty. The season after I think we only got one penalty and by the time I moved to Derby they already had a penalty taker so that was it. I would say that for every dubious penalty that was awarded there were another twenty that we should have had.

Was the move to Derby something you really wanted?

No. By that time my business was substantial so going to Derby was going to cause problems. Derby offered City more than anyone else and so I went there. We won the title in my first season – I’d only signed a contract for a year – and they were a very good side, so I stayed with them for another season. The pitch was awful – even Maine Road’s pitch was better – but we could have won the European Cup that second season. We won the first leg of a tie with Real Madrid 4-1 but I missed the return because I’d been sent off in the Hunter incident against Leeds. We lost 5-1.

They actually changed the rule after that saying it was unfair to automatically ban a player from a European game after a domestic match when the player had yet to be proved to be guilty or not guilty. There wasn’t much chance of me being ‘not guilty’ – the footage was there for everyone to see!

There was that memorable game when you came back to Maine Road and scored for Derby at the Platt Lane end of the ground. I was in the stand that day and I remember a surreal moment when City fans cheered your goal. Did that happen or is it just my memory?

Yes, it did happen. Then I think they thought: “What have we done, he’s playing for them!”

I enjoyed my football and I loved scoring so when I scored and the film shows me smiling it was because I’d scored what I thought was a good goal. I picked it up with my back to the line, went through two people and on to score the goal. I loved the goal and it is true that everyone applauded. It had nothing to do with City or revenge or anything like that. I think I enjoyed about 95% of every game I ever played. It was fun. A great way to earn a living, so on that day I was happy.

People often suggest that City sold you too soon and that had you stayed a couple of seasons longer we might have won the title ourselves. Do you hold this view?

I think if I’d have stayed and Mike Summerbee – remember he was sold a year after me – then I do think we’d have mounted a serious challenge for the title. Mike had more to offer.

After two seasons at Derby you retired, but you were still relatively young. Why?

I had about 110 people working for me and my business was taking over. I was travelling all over the country for my business and was trying to fit the football training in as well. I needed to concentrate on the business. Had I been playing in Manchester or Bolton then I may have carried on. I was only 32. Derby wanted me to stay on, and I made a promise to Dave Mackay that if I was to return to football then I’d do it for him. Tommy Docherty tried to persuade me to join United but I’d made that promise and wouldn’t do it.

You developed your business interests and horse racing over the following twenty years, but then suddenly you were back, mounting takeover of City. Why?

I wasn’t really looking to get back into the game at all during those years. I had a good and successful career outside of the game and was happy. But the takeover was one of those things that happened. I should have known that it wouldn’t work. The biggest problem we faced at the start was having to build the new Kippax Stand. We ended up spending about £16m in the end – even removing the waste from underneath the old terracing should have cost only £80,000 but ended up costing about £1.8m. I thought then that I’d always been lucky in life and then suddenly my luck had changed. Everything we tried to do became an issue and the Kippax was a bit of a millstone.

It’s extraordinary when you think that at that time Jack Walker had put some money into Blackburn and Everton had had some money put into it, and we put money into City, but prior to that no one ever put money into a football club. They bought shares but never invested, we did invest. But the financial state of the club was appalling.

It strikes me that off the pitch things did improve significantly, but on the pitch we struggled. What’s your view?

People like John Dunkerley worked very hard during that spell and the training facilities were improved and so on. Then, just when we finished the Kippax Manchester Council started to talk to me about becoming tenants of the new stadium – now that turned out to be the best thing that happened to City during the decade that followed. We spent a lot of time working with them and talking with various people to make it happen. Full marks must go to the Council for having the foresight and it became very important for City to become anchor tenants. I think I had a lot of bad luck as Chairman and things certainly didn’t work on the pitch, but I do think that was one thing that the club got right.

Why did it fail on the field?

I don’t know. Maybe the footballers didn’t enjoy playing as much as they ought to have done. We also had a few problems with managers but I’d better not get into that.

Finally, many people claim the 1970 League Cup Final was your greatest City game, do you feel that?

I don’t view it like that. I don’t think of individual games in that way. My job was to score goals and win games, and so I look at my career and see what goals I’ve scored. You have to look at the club during your time there and see what that club won and what you contributed to the overall success of the club, not necessarily individual games.

My role was to make things happen, and if I was making things happen, especially if it was causing some aggravation for the opposition, then I was happy. When you hear the opposition players shouting things like: “don’t let him turn!” that’s a real pat on the back. You know you’re getting to them.

In terms of individual games or goals… I don’t see it in those terms. In the championship season I think one of the goals I scored at West Ham (18/11/67) was the best goal I’ve ever scored. I was playing against Bobby Moore and I think I had a fantastic game but, because they are trophy winning games in their own right, cup finals tend to be remembered mostly by others.

I always think that a top class player should go on to the pitch and have enough confidence in his own ability to know that it is very rare for him to have a bad game. It’s not arrogance or anything, but it is the mark of a top class player. If you go onto the pitch feeling that then more often than not you will have a good game. The next step is to take it up the levels until you walk on to the pitch believing you’ll have a great game and score a couple of goals. At City most of us developed that confidence and on some days, when the entire team was at that level, we had some tremendous games. That Newcastle title decider was like that.