6th February is of course the anniversary of the Munich Air Disaster. Back in 2008 I researched and wrote the following 8000+ word piece on the Munich Air Disaster. It spells out the story of the disaster; the spirit of Manchester at the time and explains how the tragedy affected individuals from both Red and Blue Manchester. It’s a long read but I hope people stick with it. It’s something we should all think about and remember.

My thoughts are with the victims, their families and friends.

One event has been written about more than any other in the history of the game within the Manchester region and that event is also by far the most tragic and devastating moment in Mancunian sport. Ignoring stadium disasters such as Hillsborough, Bradford, and Bolton, the Munich Air Disaster was the worst tragedy to affect any English club. It brought the near destruction of an entire team of good quality, successful players.

The story of the disaster has been covered extensively over the years and has featured in many television documentaries and even in feature length dramatisations, however it is worth assessing the way the disaster took hold of the people of the region and how it was viewed by all Mancunians at the time.

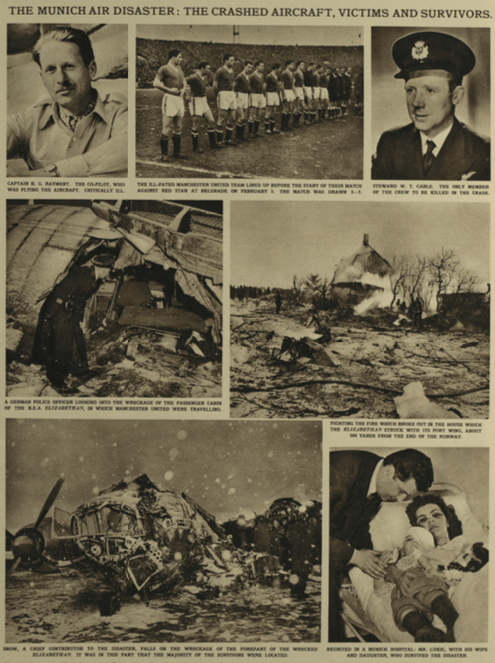

The simple facts of the story are that 23 people, including eight Manchester United players, were killed in the disaster on 6th February 1958, but the circumstances surrounding it need explaining. United had progressed to the quarter-finals of the European Cup where they were to face Red Star Belgrade on a two-legged basis. The first leg, played at Old Trafford on 14th January was watched by a crowd of around 35,000 and ended in a 2-1 victory – Eddie Colman and Bobby Charlton the scorers. The following month, on 5thFebruary, the Reds played the second leg and drew the game 3-3, thereby winning the tie 5-4 on aggregate. It was the second time United had reached the semi-final stage and there was a strong feeling this was to be United’s year, although AC Milan and Real Madrid had also reached the semi-final stage. Madrid it has to be remembered had won the competition in its first two seasons, and would ultimately win the trophy for five consecutive seasons. Madrid were a phenomenal side.

As well as their progress in Europe the Reds were also challenging for the League title and had already reached the fifth round of the FA Cup, and many of their young players were national figures.

After the game in Belgrade the Reds stayed overnight in the city. There had been an official banquet after the match and manager Matt Busby spent much of the evening in the company of Frank Swift, his former City team mate who was by this time a leading journalist, and several other journalists and friends. The journey home began the next morning (Thursday) and for many years rumours that United were under pressure to return home to ensure they were back in plenty of time for their Saturday fixture with League leaders Wolves has been suggested. Clearly the Football League would not have wanted European football to jeopardise a game that was already viewed by many as the deciding factor in the Championship race (a Wolves victory would place United eight points behind the leaders with only 13 games to go), however it is highly debateable that the League or FA would have placed pressure on United at this moment. It is possible United felt the pressure of course, as they had gone against the English authorities the previous year by entering the European Cup.

At Belgrade there were a few delays caused by lost passports and the like, however the weather was also poor. The previous day’s game had been played in wintry conditions and by the time the flight left Belgrade visibility was poor but still not bad enough to cause a cancellation. The journey back to Manchester was intended to get the players home by teatime, with a stop off at Munich for refuelling.

In Germany snow was falling and the conditions were deteriorating, however after a short refuel the plane was ready to take off again at 2pm. The pilot Captain James Thain and his co-pilot Captain Kenneth Rayment prepared for take-off with Rayment taking the controls. Thain later gave his version of what happened next:

“As Ken opened the throttles, which were between us on the central pedestal, with his right hand, I followed with my left hand. When they were fully open I tapped his hand and held the throttles in the fully open position. Ken moved his hand and I called ‘full power’ and, looking at the instruments in front of me, said ‘Temperatures and pressures correct and warning lights out’. I then called out the speed in knots as the aircraft accelerated. The engines sounded an uneven note and the needle on the port pressure gauge started to fluctuate. I felt a pain in my left hand as Ken pulled the throttles back and said ‘Abandon take-off’. I held the control column fully forward while Ken put on the brakes.

“What had happened was boost surging, which was not uncommon with Elizabethans at the time, particularly at airports like Munich, because of their height above sea level. Over-rich mixture caused the power surge, but though the engines sounded uneven there was not much danger that the take-off power of the aircraft would be affected. The Elizabethans were very powerful in their day and you could actually have taken off on one engine. Knowing that one cause of boost surging was opening the throttles too quickly, Ken said that at the start of our next run he would open the throttles a little before releasing the brakes and then continue to open them more slowly. Ken opened the throttles to twenty-eight inches, released the brakes; and off we went again.”

The plane struggled further: “I took the decision to abandon the take-off this time. We were halfway down the runway with the throttles fully open when I saw the starboard engine steady itself at fifty-seven and-a-half inches but the port pressure run to sixty inches and beyond. I wanted to discuss this with the BEA station engineer.

“The station engineer, William Black, came to the cockpit to check the trouble and we explained about the boost surging. He said it was fairly common at airports like Munich.”

The engineer explained how Thain and Rayment could overcome the problem but also suggested he could retune the engines but explained that an overnight stop would then be required. This was not something the pilot felt was necessary, and so the decision was taken to make a third attempt at take-off.

The United players, management and other passengers were in the airport building at this stage and so had to be recalled to the aircraft. In the airport building Duncan Edwards sent a telegram to his landlady saying: “All flights cancelled – stop – flying tomorrow – stop – Duncan.” Manchester Evening Chronicle journalist Alf Clarke telephoned the newspaper with similar news.

For most of the players and some of the journalists the period in the airport was typical of the experience most feel when waiting for a delayed flight. Some of the players were buying drinks and snacks, others simply sat around waiting. Journalists Franks Swift and Eric Thompson were lightening the mood. According to another journalist, Frank Taylor, in his eyewitness account of the disaster The Day A Team Died:

“The comics, Frank Swift and Eric Thompson, had taken over. Eric, small and round, had picked up Big Swifty’s overcoat and he was shuffling around the room like a lost grizzly bear, the coat almost trailing the floor, the arms hanging hugely by his sides. Big Swifty was trying to cram his massive torso into Eric’s coat. ‘Must have shrunk’ he was saying with that gormless grin so famed in the sporting world. ‘Or maybe I’ve growed on this trip’.”

Earlier Swift had entertained some of the passengers with stories from his playing career.

Once the passengers returned to the plane Thain and Rayment attempted the third – and fatal – take off. Frank Taylor’s book on the disaster has become the best eyewitness account of how the events unfolded, and he explores in detail the take off and events that followed. Suffice to say that at two minutes past three the pilots were given clearance to take off but were told that if they were not airborne by four minutes past three the clearance would become void. This suggests any take off later than four minutes past would not be allowed and a considerable wait would occur. Taylor:

“I wonder what went through their [the pilots] minds then? Did they feel under pressure? If they didn’t get the aircraft airborne within the next two minutes, they might face a much longer delay on the ground. In the passengers’ cabin, we didn’t know the pilots had been warned they had two minutes to make up their minds whether or not to go.”

The decision was taken to go and by this time the mood of many of the passengers was quite subdued. Some were extremely nervous about the flight, while others tried to focus on other things. Survivor Bill Foulkes later told journalists that the passengers had felt unsettled and that one of the players chose to move to the back of the aircraft where most of the journalists sat:

“David Pegg said ‘I’m not sitting here. It’s not safe’, and went to the back of the plane. And I seem to remember Frank Swift standing up near the back and saying something like, ‘that’s right, lads, this is the place to be’. We set off and I remember looking out of the window. They had big windows, those Elizabethans. I remember seeing the snow coming down and the slush flying about and then there was a terrible noise, the kind you might expect to hear of a car suddenly left a smooth road and started running over rocks.”

The plane’s speed had been increasing until this point and despite the general air of anxiety all had seemed well. Captain Thain later told the German inquiry his view of what happened:

“When it reached 117 knots I called out ‘V1’ [velocity one, the speed at which it is no longer safe to abandon take off] and waited for a positive indication of more speed so that I could call ‘V2’ [119 knots – the speed required before taking off]. Suddenly the needle dropped back to 112, and then 105. Ken shouted ‘Christ, we can’t make it,’ and I looked up from the instruments to see a lot of snow and a house and a tree, right in the path of the aircraft.”

Later it was discovered that the engineer had incorrectly re-fitted the air speed indicator meaning it gave an incorrect reading. From that point on the plane careered off the runway and headed towards a house positioned beyond the airport. Thain:

“The aircraft went through a fence and crossed a road and the port wing hit the house. The wing and part of the tail were torn off and the house caught fire.”

Little has been said over the years about the fate of the people living in the house at the time. The occupants were the Winkler family. The husband was out, presumably at work, and the eldest daughter was at a friend’s at the time of the crash but the girl’s mother, Anna, was at home sewing together with her three other children. According to German reports two of the children were having an afternoon nap and were thrown out of the burning house by Anna, who also escaped, while the other child – a four year old – managed to escape by crawling out through a window.

The left wing of the plane and part of the tail were ripped off the rest of the aircraft, while the cockpit smashed into a tree and the fuselage into a hut that contained a fuel-loaded truck. This exploded.

Hans Birnbaum, a Munich fuel merchant, was one of only a handful of witnesses and he said at the time:

“The visibility was poor so not many people saw what happened. I was only 200 metres away when the plane crashed and the force of the explosion of the petrol was so powerful that I was knocked down by it. When I got up I saw flames and smoke pouring out of two houses and debris flying through the air. I ran to the plane and saw the plane had broken in pieces.”

What followed was a remarkable series of brave incidents by a number of the passengers, most notably goalkeeper Harry Gregg. Gregg actually returned to the plane to rescue a baby and its mother, and is recorded as dragging Bobby Charlton and Dennis Viollet clear, and of giving assistance to other members of the flight. He has regularly disputed the tag of ‘hero’ often used by the media when describing him. In truth though he was a hero.

Emergency vehicles ultimately arrived and the passengers – both those alive and those that had passed away – were rushed to the Rechts Der Isar hospital.

At the hospital it was not immediately obvious that the patients being brought in were connected with Manchester United. As far as the doctors were concerned these were victims of an air crash and who they were was irrelevant at first, then the head of the neuro-surgical department professor Frank Kessel started to treat the patients and he immediately recognised Frank Swift. Swift, at this point, remained a major international name and was hugely popular wherever he went. He was the first English goalkeeper to appear in the Berlin Olympic stadium – playing for English champions City in a highly publicised propaganda match against a German national XI in 1937 – and was well known to Kessel as the professor had actually lived in Manchester for a while and was known to attend football matches. He knew who Swift was, although he did not quite understand why he was in Munich, and then he spotted Swift’s old City teammate Matt Busby. “Das ist ein Englische Fussball spiel” he is reported to have exclaimed as he recognised that the combination of two former City players meant this was an English football team. Inevitably it became obvious the side was United.

Swift and Busby were both still alive at this point, although Swift was badly injured and died shortly afterwards as he was being carried into the hospital. Kessel had hoped to save the former ‘keeper but sadly his main aorta artery had been severed apparently by his seat belt. Busby’s life was also in the balance and he would have the last rites administered to him twice, but eventually after 71 days he returned to Manchester.

Two other men were also struggling – players Johnny Berry and Duncan Edwards. Berry also pulled through although his playing career came to an end due to the injuries he suffered, while Edwards fought on for 15 days before he died of kidney failure. It was the saddest moment for most Mancunians as Edwards’ fight for survival had brought much hope, but the moment he passed away signalled the end of Busby’s great side.

In total twenty-three people died as a result of the air disaster. They included eight members of United’s playing staff:

Geoffrey Bent (a reserve player for the Munich trip meaning his journey was ultimately unnecessary, 25 year old Bent had earlier made 12 League appearances for the Reds)

Roger Byrne (popular captain, Byrne made a total of 277 appearances in League, Cup and Europe, and had appeared in 33 internationals – he was two days short of his 29th birthday at the time of the crash)

Eddie Colman (21 year old Colman made 107 League, Cup & European appearances)

Duncan Edwards (the most famous member of the team, 21 year old Edwards made 175 League, Cup and European appearances and had appeared in 18 internationals)

Mark Jones (24 year old Jones made 120 League, Cup and European appearances)

David Pegg (22 year old Pegg made 148 League, Cup and European appearances and had made one international appearance)

Tommy Taylor (26 year old Taylor made 189 League, Cup and European appearances and 19 internationals)

Liam ‘Billy’ Whelan (Like Bent 22 year old Whelan was a reserve for the Belgrade game, in total he had appeared in 96 League, Cup and European games, netting 52 goals and made 5 Eire international appearances)

Three members of United staff:

Walter Crickmer (United secretary and manager in 1931-32 & 1937-45)

Tom Curry (trainer and former Newcastle & Stockport player)

Bert Whalley (coach and former Stalybridge Celtic and United player). You can read more about Bert Whalley (who was a friend of my grandad’s) here:

Eight journalists:

Alf Clarke (Manchester Evening Chronicle)

Don Davies (Manchester Guardian)

George Follows (Daily Herald)

Tom Jackson (Manchester Evening News)

Archie Ledbrooke (Daily Mirror)

Henry Rose (Daily Express)

Frank Swift (News of the World & former City goalkeeper and England captain)

Eric Thompson (Daily Mail)

The other victims were:

Tom Cable (steward)

Capt Kenneth Rayment (co-pilot)

Willie Satinoff (Manchester businessman)

Bela Miklos (travel agent)

The following all survived the crash:

Johnny Berry – was in a coma for two months following the disaster and was never able to resume his playing career. He suffered brain damage and according to other survivors his hand-eye co-ordination had gone. Within 12 months of the disaster he and his family were ordered to leave their club house and his employment cards arrived in the post. Berry’s problems continued throughout his life (he passed away in 1994) and understandably his wife never forgave United for their treatment of the family.

Jackie Blanchflower – suffered renal damage and various broken bones, including his pelvis, and despite his youth (he was only 25) he was unable to play again. He had been destined to play for Northern Ireland in the 1958 World Cup finals but struggled to make a decent non-footballing career instead. Like Berry, Blanchflower was told to leave his club house a few months after the disaster, even though his wife was pregnant and it was clear the family would struggle. New Chairman Louis Edwards gave him a job loading pies on to lorries at his meat factory and it was reported in The Lost Babes that he refused to go to Old Trafford after being turned away when he asked for match tickets for his doctor. He passed away in 1998.

Matt Busby – after a long fight to regain fitness Busby returned to his role as United’s manager and ultimately created a new side which, in 1968, became the first English side to win the European Cup. He was awarded the CBE in 1958 and then was knighted in 1968. He remained a key presence at Old Trafford until his death in 1994.

Bobby Charlton – went on to become recognised as one of United and England’s greatest players. He was part of Busby’s new side during the Sixties and featured in the successes of that side. He was a member of the 1966 World Cup winning team.

Bill Foulkes – As with Charlton he managed to return to action and feature in the new United, winning the European Cup in 1968.

Harry Gregg – Appeared in the 1958 FA Cup final and remained with United until 1966. Had a spell as United goalkeeping coach from 1978 until 1981. He has remained keen to challenge perceptions of Munich throughout his life and has tried to fight to help the families of the victims and the survivors – the majority of whom found life extremely difficult after the disaster.

Ken Morgans – although he returned to action in April 1958 he was never able to establish himself in the side post-Munich. In March 1961 he was transferred to Swansea and also had a spell at Newport County.

Albert Scanlon – had been left for dead initially as rescue workers searched for those who looked more likely to survive. He suffered a fractured skull but managed to return to England within a month. Sadly he was transferred out of United in November 1960 and felt he had been betrayed by the club, in particular by new Chairman Louis Edwards and by Matt Busby. In later life Scanlon worked 12 hour shifts as a security guard.

Dennis Viollet – resurrected his career and played in the 1958 FA Cup final, however in January 1962 he was sold to Stoke City. According to friends his personality and approach to life changed significantly after Munich. In later life he suffered with a brain tumour – many believe this had been caused by the bang to his head he received at Munich – and he passed away in the States during 1999.

Ray Wood – By the time of Munich the 1957 FA Cup final ‘keeper Wood had lost his place to Gregg and inevitably, post Munich, the ‘keeper was unable to regain his position – he made one first team appearances (a 4-0 defeat at Wolves on 4/10/58). He was transferred to Huddersfield in December 1958 and played over 200 league games for them. He passed away in 2002.

The other survivors were:

- Frank Taylor – the only journalist to survive and he went on to write the highly acclaimed The Day A Team Died. He was also awarded the OBE and passed away in 2002.

- Peter Howard – Daily Mail Photographer

- Ted Ellyard – Photographer

- Mrs Vera Lukic and baby daughter Venona – Passengers (saved by Manchester United player Harry Gregg)

- Eleanor Miklos – Wife of the travel agent that arranged the trip who died in the crash

- George ‘Bill’ Rodgers – Radio officer

- Belosja Tomasevic – Passenger

- James Thain – Captain

- Rosemary Cheverton – Stewardess

- Margaret Bellis – Stewardess

Over the years Munich has come to mean different things. For some it is a strong reminder of the pioneering spirit of Fifties United and of the quality of those unfortunate young men who passed away in such devastating circumstances. Others have seen it as an important step towards the globalisation of the United name and brand. In fact there are some that see the disaster as a means of capitalising on tragedy and in Jeff Connor’s publication The Lost Babes he explores in detail the way the disaster has been used to generate income for others – he talks of the 1998 benefit match which raised around £1m but over £90,000 was paid to Eric Cantona’s agent for expenses in relation to the Frenchman’s appearance in the game – and of the use of Munich in merchandise, museums, television and other areas of the media.

For most true Mancunian United-supporting families it is the players they think of first, rather than the specifics of the tragedy. Actor and Salford born United fan Christopher Eccleston talked of the players during an interview with Denis Campbell in 2002:

“Some of my earliest memories are of my dad talking about the Babes, specifically Duncan Edwards. ‘He was a man at 16,’ he always said. He was a great guy but kept his feelings to himself, but at any mention of that team he suddenly became filled with emotion.

“My mum was an Old Trafford trolley-dolly. She used to push a trolley round the side of the pitch selling Bovril. Just recently she said, very casually, ‘When we finished work we used to see Duncan standing at the bus stop after the game eating fish and chips.’ Can you imagine Ryan Giggs doing that? My dad would talk about them as players while my mum talked about their personalities, like ‘Roger Byrne’s very good looking but you can tell he’s moody’.”

Back in 1958 when the first news of the crash filtered back to Manchester, the city was in shock. No one could understand or accept what they were hearing. Former City Chairman Eric Alexander, who in 1958 was part of City’s ground committee and was also working in the area, remembers the moment he heard the news:

“I heard people in the street on Deansgate shouting. I was struggling to make out what they were saying but it sounded as if something had happened to United. The noise and emotion ran high and I had to find out. I rushed out on to the street and heard what had happened. It made me feel sick. It was one of those moments that you dread. It was awful.

“It affected everybody in Manchester. No question. We knew the players obviously, but we also knew the journalists. We all lost something very significant that day.”

By 6pm a special edition of Alf Clarke’s newspaper, the Manchester Evening Chronicle, was on sale:

“About 28 people, including members of the Manchester United football team, club officials, and journalists are feared to have been killed when a BEA Elizabethan airliner crashed soon after take-off in a snowstorm at Munich airport this afternoon. It is understood there may be about 16 survivors. Four of them are crew members.”

It also included Clarke’s match report and referred to his telephone conversation earlier in the afternoon.

Gradually accurate information started to emerge, but the strength of feeling was such that thousands of Mancunians walked the streets of the city dazed, shocked and confused. Clearly, the death of any of those players in tragic circumstances would have been greeted with a shared feeling of grief but the size of the disaster and the impact it had on football and on the city reached incredible levels. Supporters of all sides felt the grief and the relationship between the Manchester region clubs at this point was not a difficult one. There were rivalries of course, but with City and United both sets of supporters shared the pain of the tragedy. Matt Busby and Frank Swift were tremendous City heroes, while many of the players had grown up in the city and were known to Red and Blue alike. Viollet and Scanlon had been City fans as boys, while Byrne came from Gorton.

In the Busby household as the news filtered through members of his family and Swift’s gathered on the day of the disaster. Little was known, but the news did come through that Busby was amongst the survivors. The Manchester Evening Chronicle reported the reaction:

“Said Mrs. Busby: ‘Thanks God he’s safe’ but the family could not celebrate. They did not know whether he had been injured and also in the house was Mrs. Frank Swift, upset and ill with no news of her husband. Finally Mrs. Swift’s son-in-law came to the house and said he would break the news to her that her husband was unaccounted for. He drove her home in his car.”

Swift was of course a journalist by this point, and each of the journalists were major local figures. Don Davies, Henry Rose, Archie Ledbrooke and the others were well known and popular reporters who had covered the game in Manchester for many, many years. Davies, who went under the name of an Old International, had reported on almost every significant moment to affect Mancunian football for years.

Bert Trautmann, City’s German goalkeeper, heard the news of the crash at home. He was listening to the radio and was immediately engulfed with sadness. One of the victims, Frank Swift, had been his predecessor at City, but most of the other victims were also known to him personally. Once he managed to gather his thoughts he started to consider how his understudy Steve Fleet was feeling.

Steve’s story is typical of the way the players felt: “It is one of those events that make you realise that life itself is a greater game than football. It matures you. It makes you realise what life is all about and though it’s difficult at the time to understand, it did actually put football in its place. Football was not important in the weeks that followed the crash.

“I had lots of friends at United, but Eddie Colman was my best friend. Up to his death we were as close as anybody could be. He was going to be the best man at my wedding. When he died it was terrible. Eddie lived in Archie Street – the inspiration for Coronation Street – and I lived close by. On the night of the crash we all congregated at his house and we waited for news. None of us had a telephone in those days, so the only way we could find out what was happening was by going to the off-licence down the road and call United. I kept going off to do it. Les Olive was answering the ‘phone at Old Trafford and he said to me ‘Steve, I know you’re very close to his family, can you tell them that Eddie’s gone’. I then had to go back to Eddie’s house and tell his mum and dad. Something you never think you have to do, especially at that age. His dad couldn’t accept it. He said I must be wrong. He went down to the off-licence and made a call himself.

“It was awful, but that was the way it was for a lot of people.”

The following day the City players met at Maine Road. Bert Trautmann rushed to see Steve Fleet: “Bert understood more than anyone how I felt about losing Eddie. He taught me how to handle grief and come to terms with it. It was not easy but Bert had such humility and a caring attitude he helped me tremendously to overcome one of the worst periods of my life. He also offered to help United in any way he could. You see, we all knew the United players. We’d socialise with them, and they were just like us. Bobby Charlton, when he was living in digs, would sometimes come to our house for his tea. We were all close – Red or Blue didn’t come into it.”

German-national Bert contacted United and offered to help with translation, contacts and with whatever the Reds felt they needed.

Despite their grief, the City players were told they had to carry on with their own preparations for Saturday’s League game at Spurs. Cliff Lloyd, secretary of the Manchester-based PFA, had called for the suspension of the weekend’s games –something City’s players, and those of other clubs in the region desperately wanted – but within 24 hours of the crash the League insisted that only United’s game would be called off.

Reluctantly, the Blues travelled to London on Friday 9th. It is known that later that day the City players went to a cinema in North London with the hope of watching the latest newsreel footage showing the tragic scenes however, according to British Movietone, newsreel footage did not arrive until four days after the disaster and so the players could only wonder what the devastating scenes were like. Although City players do hold a view that they saw some crash related footage that night in London. City were to play at Tottenham the following day, and were staying overnight in the capital. They felt isolated from the news and changed their routine in the hope that they could find out all they could.

Inevitably at Tottenham the players wore black armbands and, full of emotion, they lined up for a two-minute silence – impeccably observed by all fans. This silence was more personal than any the players had previously been involved with – only four days later Ken Branagan, Dave Ewing, Joe Hayes, Roy Little and others would attend the funeral of Gorton born United captain Roger Byrne. It wasn’t the only funeral they attended, but it does indicate that the players’ thoughts were hardly on a game that most players across the country had wanted called off.

Understandably the crash affected the City team that day and the Spurs game ended in a 5-1 defeat.

Similar scenes appeared at football matches across the country and locally Bury faced Oldham at Gigg Lane and the players and spectators stood in two minutes silence prior to kick-off as a mark of respect for the Munich victims. The Bury Silver Band played ‘Abide with me’.

Many of the region’s players mixed socially with United’s. Other victims and survivors had grown up in the city and were known to Red and Blue alike. United’s Viollet and Scanlon had been City fans as boys.

That evening it was reported that UEFA were considering what to do with the European Cup semi finals. Real Madrid had stated they felt the competition should be suspended and that the Reds should be awarded the European Cup – this was a generous move – but UEFA did not want to do that. Instead, UEFA said they would be speaking with the FA about the selection of a team to replace United in the competition. UEFA made it clear they wanted City to take United’s place, while the Blues immediately made it known that they would not be interested in taking United’s place, and that City would do all they could to help the Reds compete in the competition. Eric Alexander:

“Our thoughts were with United. They had to take part. Part of the recovery process had to be United’s return to action – all Mancunians knew that – and we wanted to do all we could to help them go forward.”

The FA’s response was a surprising one and, when reported, it was said that the FA had stated that the decision would be theirs, not UEFA’s. Fortunately, common sense prevailed and the Reds were able to compete, however in the 1990s social commentators and writers talked of this period cynically and gave the impression that somehow City had tried to take some glory and had proactively pushed themselves forward as European replacements. This is totally unfair but the comment does show how much society changed in the decades after the disaster. Many football followers use the term ‘Munich’ as an insult, while others claim the Blues did not support United in their hour of need and tried to gain reflected glory via the European offer. The views of both groups are totally abhorrent.

The region was in a state of combined grief, and then the bodies started to be returned to Manchester. The Old Trafford gymnasium became a makeshift mortuary, while families made plans. Thousands of supporters, rival fans, and ordinary supporters gathered to pay their last respects and each funeral saw scenes of Mancunians lining roadsides as funeral processions passed by.

The story dominated every aspect of Manchester life and for those who had never quite grasped what the game was about and why it was so important to the region, this terrible disaster soon brought understanding, and it has to be stressed that this awful tragedy was not simply one affecting a single football team. It affected an entire city, region, and in many ways a nation. Many of the players were major international footballers, but more than that many of the other victims were highly respected, renowned journalists with a real passion for Manchester and its people. Daily Express journalist Geoffrey Mather provides his view of how the news filtered through the newspaper industry on his website www.northtrek.plus.com:

“As news spread, the city went silent. The grief settled like a fog: it was everywhere. Survivors were struggling for life, manager Matt Busby among them. I was features editor of the Daily Express in Manchester. I was in the office being told by the then editor, Roger Wood, that I would be in charge of all inside pages apart from Sport. I could call on any sub-editor on the editorial floor whenever I liked.

“The London editor, Sir Edward Pickering, was visiting at the time and decisions came quickly. William Hickey, normally on Page 3, was relegated to Page 13. Virtually the whole of the paper was United. I protested about my role. ‘I know nothing about football’ I argued. Roger Wood brushed that aside – ‘I will put someone from Sport in a seat behind you’. And so the long night began and decisions made at that early stage paid off. There were not to be any edition times. The pages would roll as they were made ready. The paper churned out all night long. It was a superb operation on the part of staff. I lost count of the number of pages prepared, run, re-done. At some late stage – a landmark – I had a half page of thumbnail pictures of those involved. The Daily Mail people were said to be reading our first edition to see whether their own man was alive.

“Henry Rose, best-known of Northern sports writers, had gone down with the Busby Babes. Esther Rose, his niece, was the only one on the editorial floor who did not know this. When she was finally told, she was crying as she was led out of the office. Rose’s executive chair was empty. His was a considerable presence whether in the building or Press box. The line-up as his funeral went by the office days later was almost Presidential.”

Rose’s funeral was the largest of the non-United players. Express journalist Desmond Hackett wrote a moving tribute to him and it is recorded that taxi drivers offered their services free to anyone who was going to the funeral. The funeral procession travelled by Rose’s former office – his work place was actually every significant football ground in the country – the impressive glass fronted Daily Express building in Great Ancoats, and then travelled on to Southern Cemetery, close to Maine Road where some of the other victims, would be buried and where the great Billy Meredith would also be buried the following April.

Understandably, five decades later, the air crash still bears significance at Old Trafford. The Manchester United museum understandably pays tribute to the victims, but so does the Manchester City museum at the City of Manchester Stadium with a timeline recording the victims. This is significant because the disaster touched all Mancunians regardless of team supported, or played for.

Surprisingly, considering the strong feelings of the supporters of all of the region’s clubs, the footballing authorities seemed to misjudge the mood. Not only had they refused to call off all games scheduled for the Saturday following the disaster, but they also made plans for the continuation of all competitions United were involved with. The decision was taken to progress with the League.

Inevitably Manchester and football had to keep going although, understandably, United’s game against Wolves was cancelled and their FA Cup tie against Sheffield Wednesday was delayed by four days. In between the fixtures of all other clubs continued as normal and the first senior match to be played within Manchester by either United or City was the Blues game against Birmingham City on 15th February 1958. This match has largely been forgotten by the media, but as the first game played after Munich the details of the day need to be remembered.

It was a deeply emotional affair, with few in the mood for football. It is clear there was no appetite amongst fans for the Birmingham game. It felt wrong to be playing an important match while people were still fighting for their lives, and others were being buried. Significantly, a lower crowd than usual – only 23,461 – attended Maine Road for this fixture. City’s average for the six previous home matches had been 43,000, and the season’s average would be 32,765.

The match programme was full of tributes with every editorial space, other than the Birmingham page and the team sheet, being given over to the tragedy. There were photographs of all the victims. The programme editor accurately wrote:

“Next to Old Trafford, the impact of the Munich air disaster has been felt nowhere more severely nor with more regret than here at Maine Road. Players, officials and sports writers on that ill-fated plane were our friends and yours.”

City Chairman Alan Douglas added:

“City are convinced United will recover and eventually return to their exalted place in the world of football. And if we can do anything to help them in any way, however small, to achieve that objective, we shall regard it as a privilege to do it.”

Captain Dave Ewing talked of the United players:

“On and off the field they were a grand bunch of fellows, and it is impossible to realise we shall never see some of them again.”

Former captain Roy Paul’s comments included mention of the press:

“whom I knew intimately and for whom I had such a high regard. They all had a part to play in this great game of ours, and right well they played it. We shall miss them all.”

This was still an emotional time for all Mancunians. The tragedy seemed to touch each and every Mancunian personally, and inevitably the game itself was played in an extremely mournful atmosphere. Abide with Me, with soloist Sylvia Farmer, was played by the Beswick Prize Band pre-match and every fan stood, head bowed to remember Manchester’s victims. City fan Dave Wallace writing in Century City talks of the game:

“It was pouring down. I did not switch to the Kippax but watched it from the perimeter wall at the Scoreboard End. The band played Abide With Me and all in the Main Stand stood up removed their hats and sang it with their heads bowed. It made the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. The rain continued unabated and the game was called off in the fortieth minute, the pitch a quagmire. It was as though the heavens were sending a tearful message of sympathy to Manchester.”

The heavy rain and miserable atmosphere proved to all that life was more important than a game of football.

United Chairman Harold Hardman and new secretary Les Olive were guests of honour, and they were encouraged by City to approach several City players to fill the gaps left by the crash. It was clearly something they did not want to do but it was absolutely vital, and attempts were made to sign City’s Irish international Fionan ‘Paddy’ Fagan but for unknown reasons this failed. Many clubs, most memorably City, Liverpool, and Nottingham Forest, offered United whatever assistance they could.

The Munich disaster affected all Mancunians and all involved with sport in Manchester. In the years that have followed, the City-Birmingham game has largely been forgotten. As with all abandoned games it was wiped from the records, however perhaps there has also been a subconscious effort to forget the day as it was such a painful one. Manchester had not yet found the strength to carry on and look to the future – that would come with United’s first home game.

On Wednesday 19th February an emotional night saw the Reds compete in their first post-Munich match. A highly emotional evening saw Survivors Harry Gregg and Bill Foulkes take to the field with new signings Ernie Taylor and Stan Crowther (both given special dispensation to play in the FA Cup after competing for other clubs), and relatively inexperienced players Ian Greaves, Freddie Goodwin, Ron Cope, Colin Webster, Alex Dawson, Mark Pearson and Shay Brennan. Ian Greaves later admitted how he felt replacing Roger Byrne:

“I can remember the dressing room was very quiet. I couldn’t get Roger out of my mind; I was getting changed where he would have sat. I was wearing his shirt…”

The game was watched by a crowd of 59,848 – the second highest home crowd of the season (63,347 witnessed the derby with City in August), and only United’s fifth domestic attendance over 50,000 at this point in the season. This was 6,000 more than the previous cup tie and over 18,000 more than the previous home League game against Bolton. Many non-football followers attended that night, as did the supporters of other clubs. The feeling was that everybody wanted to help the Reds.

The game ended 3-0 to the Reds with goals from Brennan (2) and Dawson, and three days later the first home League game after Munich ended in a 1-1 draw against Nottingham Forest before 66,124 – this would prove to be United’s biggest Old Trafford attendance of the 1950s.

Much has been made in the more recent past about the effect of Munich on United and it is clear in pure statistical terms that the disaster did have an initial impact on attendances. The average crowd for the seasons prior to Munich stood at 35,458 (1953-4), 35,960 (1954-55), 39,254 (1955-56) and 45,481 (1956-57). For the 1957-58 season the final average was 46,073, but this rocketed to 53,258 for 1958-59, however by 1962 support had dropped back to a more typical figure of 33,491 (fifth best in the League). This was one of three seasons in the 1960s when support averaged less than 40,000 and it was only when the Reds found major success under Busby in the mid to late Sixties that crowds reached in excess of 50,000 on a regular basis. In general though the Reds spent most of the 15 years post-Munich as one of football’s top three best-supported sides and then in the period post 1972 they tended to be the best supported club year after year.

In terms of on the pitch performance and atmosphere around United it is clear the disaster continued to have an effect for many years. In 1958 itself the Reds were swept along on a tide of emotion to the 1958 FA Cup final, but their European campaign ended with a 5-2 aggregate defeat to AC Milan.

The FA Cup final saw them defeated 2-0 by Bolton and Tony Pawson, writing in the Observer, gave a realistic assessment of the game:

”In prospect yesterday’s Cup Final was more likely to be distinguished by its emotional impact than the quality of the football. So it proved, except that there was little of the expected excitement. Manchester rarely seemed likely to crown their wonderful recovery with this last triumph. Bolton are essentially an effective rather than an attractive team, and they won because they were always marking more closely, tackling harder, and, above all, moving more quickly to meet the ball. Their play was, in fact, ideally suited to upset their opponents.

“Manchester United, who had won through to the Final as much by their enthusiasm and spirit as by their skill, now found themselves outmatched in determination, in strength and in the will to win. Tactically, too, Bolton were their masters, for they kept with relentless persistence to a plan that was simple and effective. Edwards, keeping always at Taylor’s side, cut him off from the ball, destroying at once the cohesion of Manchester’s attack. Without the inspiration of Taylor’s constructive and cunning passes, United’s forwards had nothing to offer except the power and thrust of Charlton, who was left to challenge on his own the competent Bolton defence.

“Cope was outstanding in Manchester’s defence, playing with a coolness and command that was lacking in the fretful play of their backs and wing-halves.”

Pawson added: “For Manchester it was a day of dust and ashes as their weaknesses were ruthlessly exposed by opponents who harried them from start to finish. It wasn’t that they were overawed by the occasion, simply that they lacked the ability to counter so fierce a challenge.

“There remained Charlton to save the game for United, and it is a measure of the remarkable advance he has made that he came near to doing it. Bolton’s superiority was unquestioned, but twice he nearly snatched the game from them. In the first half he sent Hopkinson diving to save, brilliantly, a shot of tremendous power; in the second, a shot which might have turned the game thundered against the inside of the post and rebounded to the goalkeeper. A year ago Charlton would have manoeuvred the ball awkwardly and automatically to his left, but these shots were hit with equal ease and force with either foot. In midfield his bursts of speed and close control of the ball made him a lonely threat throughout. Surprisingly, however, as the game progressed, he lay deeper and deeper, giving Bolton, who were otherwise untroubled, too much time to guard against his sudden raids.

“From the start it was clear that Bolton were setting too fast a pace for United; and within minutes they were ahead. A long pass from Banks to Birch, a centre to the far post, and Lofthouse came near to rushing the ball in as Gregg hesitated. The corner kept Bolton on the attack, and when Taylor headed clear, Edwards sent the ball back across the goal and Lofthouse, again at the far post, ran in to glide it home. Birch continued to trouble the defence, and once when he varied his long centres by turning inwards himself and shooting left-footed, Gregg for the first time took the ball with his usual confidence. United had their chance at last as Taylor, winning the ball for once, sent a measured pass out to Webster, and Viollet drove the ball over from close in as it was pulled back to him. In the main, however, play was disjointed and destructive, with Bolton neater and more frequent in their attacks.”

United trainer Jack Crompton felt United were never going to win that final: “Coming back and finding what was left of the team. It was a difficult time. We’d lost the final before we even went to Wembley, and once it started we were never in it. It was all Bolton, even though it was a foul on Gregg when Nat Lofthouse scored.”

1 Comment